THE SECOND BATTALION ROYAL DUBLIN FUSILIERS

IN THE SOUTH AFRICAN WAR

W. & D. Downey.

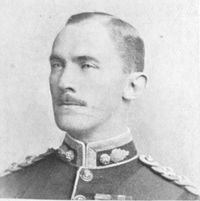

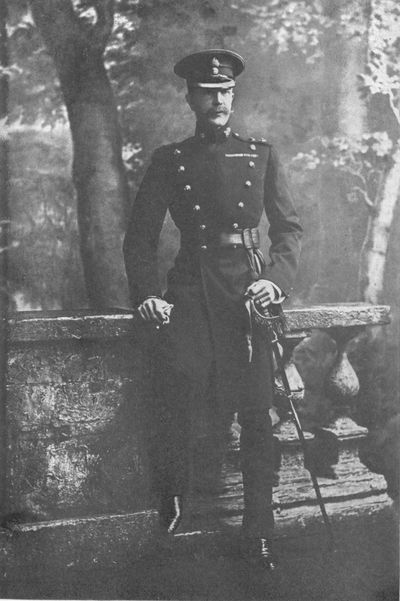

H.R.H. THE DUKE OF CONNAUGHT AND STRATHEARN, K.G.,

Commander-in-Chief of The Mediterranean Forces, and Colonel-in-Chief of The Royal Dublin Fusiliers.

THE SECOND BATTALION

ROYAL DUBLIN FUSILIERS

IN THE SOUTH AFRICAN WAR

WITH A DESCRIPTION OF THE OPERATIONS

IN THE ADEN HINTERLAND

By Majors C. F. ROMER & A. E. MAINWARING

LONDON: A. L. HUMPHREYS, 187 PICCADILLY, W.

1908

PREFACE

The 2nd Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers is one of the oldest regiments in the service. It was raised in February and March, 1661, to form the garrison of Bombay, which had been ceded to the Crown as part of the dowry of the Infanta of Portugal, on her marriage with King Charles II. It then consisted of four companies, the establishment of each being one captain, one lieutenant, one ensign, two sergeants, three corporals, two drummers, and 100 privates, and arrived at Bombay on September 18th, 1662, under the command of Sir Abraham Shipman. Under various titles it took part in nearly all the continuous fighting of which the history of India of those days is principally composed, being generally known as the Bombay European Regiment, until in March, 1843, it was granted the title of 1st Bombay Fusiliers. In 1862 the regiment was transferred to the Crown, when the word ‘Royal’ was added to its title, and it became known as the 103rd Regiment, The Royal Bombay Fusiliers. In 1873 the regiment was linked to the Royal Madras Fusiliers, whose history up to that time had been very similar to its own. By General Order 41, of 1881, the titles of the two regiments underwent yet another change, when they became known by their present names, the 1st and 2nd Battalions Royal Dublin Fusiliers.

The 2nd Battalion first left India for home service on January 2nd, 1871, when it embarked on H.M.S. Malabar, arriving at Portsmouth Harbour about 8 a.m. on February 4th, and was stationed at Parkhurst. Its home service lasted until 1884, when it embarked for Gibraltar. In 1885 it moved to Egypt, and in 1886 to India, where it was quartered until 1897, when it was suddenly ordered to South Africa, on account of our strained relations with the Transvaal Republic. On arrival at Durban, however, the difficulties had been settled for the time being, and the regiment was quartered at Pietermaritzburg until it moved up to Dundee in 1899, just previous to the outbreak of war.

The late Major-General Penn-Symons assumed command of the Natal force in 1897, and from that date commenced the firm friendship and mutual regard between him and the regiment, which lasted without a break until the day when he met his death at Talana. The interest he took in the battalion and his zeal resulted in a stiff training, but a training for which we must always feel grateful, and remember with kind, if sad, recollections. It was his custom to see a great deal of the regiments under his command, and he very frequently lunched with us, by which means he not only made himself personally acquainted with the characters of the officers of the regiment, but also had an opportunity of seeing for himself the deep esprit de corps which existed in it, and without which no regiment can ever hope to successfully overcome the perils and hardships incidental to active service.

As the shadow of the coming war grew dark and ever darker on the Northern horizon, the disposition of the Natal troops underwent some change, and General Penn-Symons’ brigade, of which the regiment formed part, was moved up to Dundee, and was there stationed at the time of the outbreak of hostilities. In spite of the long roll of battle honours, of which both battalions are so justly proud, the South African Campaign was the first active service either had seen under their present titles, and the first opportunity afforded them of making those new titles as celebrated as the old ones which had done so much towards the acquisition of our Indian Empire. Imbued with these feelings the regiment lay camped within full view of Talana Hill, waiting the oncoming of the huge wave of invasion which was so shortly to sweep over the borders, engulf Ladysmith, and threaten to reach Maritzburg itself. But that was not to be. Its force was spent long ere it reached the capital, and a few horsemen near the banks of the Mooi River marked the line of its utmost limit in this direction.

The present work only claims to be a plain soldier’s narrative of the part taken by the 2nd Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers in stemming this rush, and its subsequent efforts, its grim fights on the hills which fringe the borders of the River Tugela, its long and weary marches across the rolling uplands of the Transvaal, and its subsequent monotonous life of constant vigil in fort and blockhouse, and on escort duty.

All five battalions took part in the war. The 1st sailed from Ireland on November 10th, 1899, and sent three companies under Major Hicks to strengthen the 2nd Battalion. They arrived in time to share in the action at Colenso on December 15th, and all the subsequent fighting which finally resulted in the relief of Ladysmith, after which they returned to the headquarters of the 1st Battalion, which formed part of the Natal army under General Sir Redvers Buller, and later on advanced through Laing’s Nek and Alleman’s Nek into the Transvaal. The 3rd Battalion sent a very strong draft of its reserve, and the 4th and 5th Battalions volunteered and came out to the front, where they rendered most excellent service. In addition to the battalions there were a good many officers of one or other battalion employed in various ways in the huge theatre of operations. Major Godley and Major Pilson had been selected for special service before the war, and the former served in Mafeking during the siege, while the latter served under General Plumer in his endeavours to raise it. Captain Kinsman also served with the latter force. Major Rutherford, Adjutant of the Ceylon Volunteers, arrived in command of the contingent from that corps. Lieutenants Cory and Taylor served with the Mounted Infantry most of the time, as did Lieutenants Garvice, Grimshaw, and Frankland, after the capture of Pretoria, while Captain Carington Smith’s share in the war is briefly stated later on. Captain MacBean was on the staff until he was killed at Nooitgedacht. The M.I. of the regiment served with great distinction, and it is regretted that it is impossible to include an account of the many actions and marches in which they took part, but the present volume deals almost exclusively with the battalion as a battalion.

The authors are desirous of expressing their most hearty and cordial thanks to all those who have assisted them in the preparation of this volume. They are especially indebted to Colonel H. Tempest Hicks, C.B., without whose co-operation the work could not have been carried out, for the loan of his diary, and for the sketches and many of the photographs. To Colonel F. P. English, D.S.O., for the extracts from his diary containing an account of the operations in the Aden Hinterland and photographs. To Captain L. F. Renny for his Ladysmith notes. Also to Sergeant-Major C. V. Brumby, Quartermaster-Sergeant Purcell, and Mr. French (late Quartermaster-Sergeant), for assistance in collecting data, compiling the appendix, and for photographs, respectively.

C. F. ROMER.

A. E. MAINWARING.

CONTENTS

CHAP.PAGE

- TALANA

- THE RETREAT FROM DUNDEE

- FROM COLENSO TO ESTCOURT

- ESTCOURT AND FRERE

- THE BATTLE OF COLENSO

- VENTER’S SPRUIT

- VAAL KRANTZ

- HART’S AND PIETER’S HILLS—THE RELIEF OF LADYSMITH

- THE SIEGE OF LADYSMITH

- ALIWAL NORTH AND FOURTEEN STREAMS

PART II.—TREKKING.

- FROM VRYBURG TO HEIDELBERG

- HEIDELBERG

- AFTER DE WET

- SEPTEMBER IN THE GATSRAND

- FREDERICKSTADT—KLIP RIVER—THE LOSBERG

- BURIED TREASURE—THE EASTERN TRANSVAAL—THE KRUGERSDORP DEFENCES

- THE LAST TWELVE MONTHS

PART III.

ILLUSTRATIONS

FULL-PAGE PLATES.

- H.R.H. THE DUKE OF CONNAUGHT AND STRATHEARN, K.G., COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF OF THE MEDITERRANEAN FORCES, AND COLONEL-IN-CHIEF OF THE ROYAL DUBLIN FUSILIERS

- REGIMENTAL BOOK-PLATE

- CASUALTIES AT TALANA

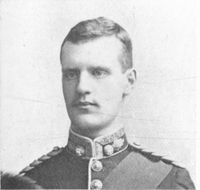

- MAJOR-GENERAL C. D. COOPER, C.B., COMMANDING 2ND ROYAL DUBLIN FUSILIERS IN NATAL

- CAPTAIN C. F. ROMER AND CAPTAIN E. FETHERSTONHAUGH

- GENERAL HART’S FLANK ATTACK FROM THE BOERS’ POINT OF VIEW (PLAN)

- CASUALTIES AT COLENSO

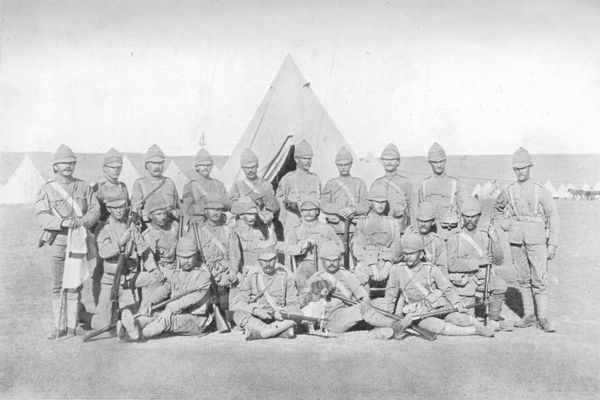

- GROUP OF TWENTY SERGEANTS TAKEN AFTER THE BATTLE OF COLENSO, ALL THAT REMAINED OF FORTY-EIGHT WHO LEFT MARITZBURG

- CASUALTIES AT TUGELA HEIGHTS

- TAKING FOURTEEN STREAMS (PLAN)

- MISCELLANEOUS CASUALTIES

- COLONEL H. TEMPEST HICKS, C.B., COMMANDING 2ND ROYAL DUBLIN FUSILIERS, MARCH, 1900—MARCH, 1904

- PLAN OF POSITION AT ZUIKERBOSCH

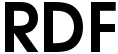

- PLAN OF BATTLE OF FREDERICKSTADT

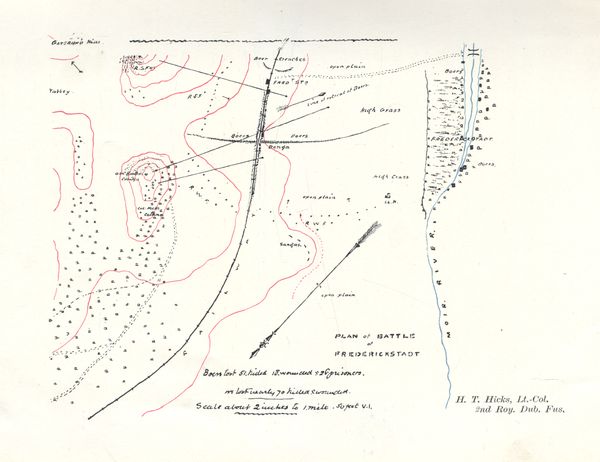

- SKETCH PLAN OF KILMARNOCK HOUSE AND FORTIFICATIONS

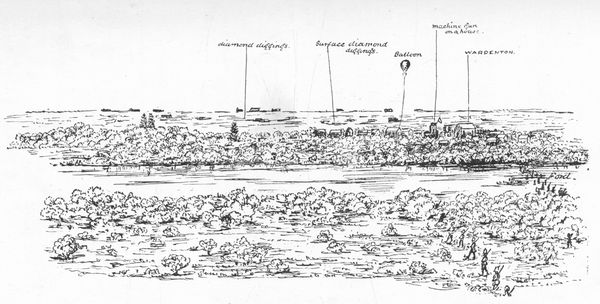

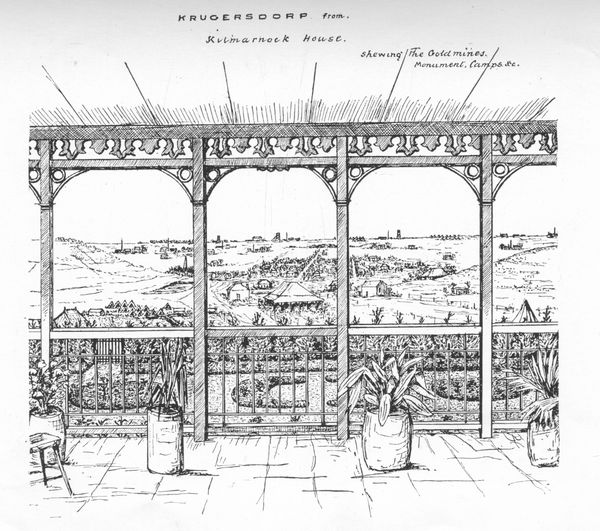

- KRUGERSDORP FROM KILMARNOCK HOUSE

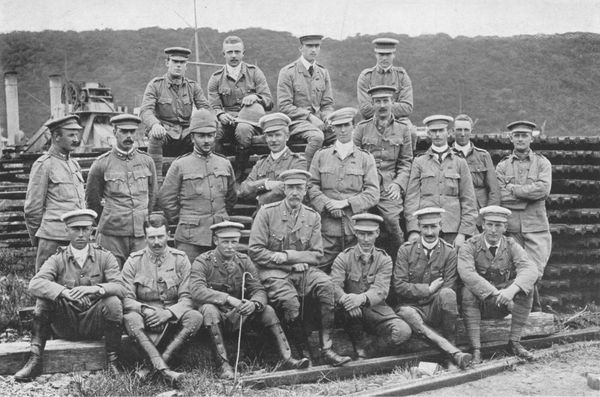

- OFFICERS OF THE 2ND BATTALION ROYAL DUBLIN FUSILIERS WHO EMBARKED FOR ADEN

- THE MEMORIAL ARCH, DUBLIN

- THE SOUTH AFRICAN MEMORIAL, NATAL

ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT.

- THE LAST RITES

- ARMOURER-SERGEANT WAITE—’DELENDA EST CARTHAGO’

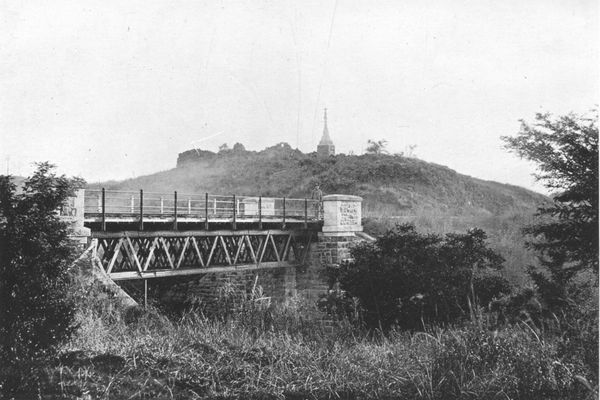

- RAILWAY BRIDGE AT COLENSO

- BOER TRENCHES, COLENSO

- BRINGING DOWN THE WOUNDED

- AFTER THE FIGHT

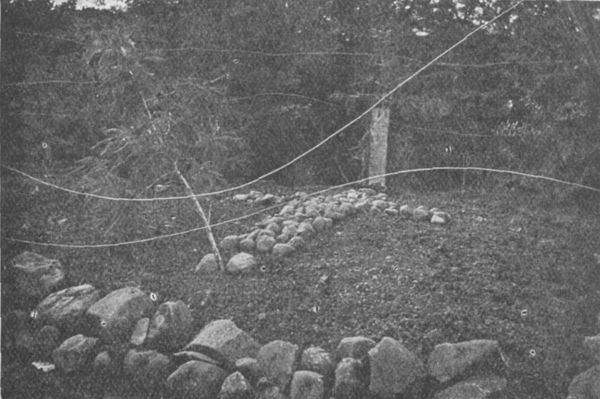

- THE GRAVE OF COLONEL SITWELL AND CAPTAIN MAITLAND, GORDON HIGHLANDERS (ATTACHED), NEAR RAILWAY AT PIETER’S HILL

- PIETER’S HILL, FEB. 27TH, 1900

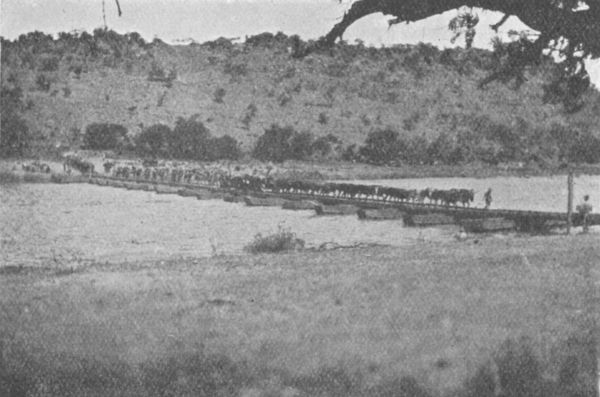

- PONTOON BRIDGE, RIVER TUGELA, FEB. 28TH, 1900

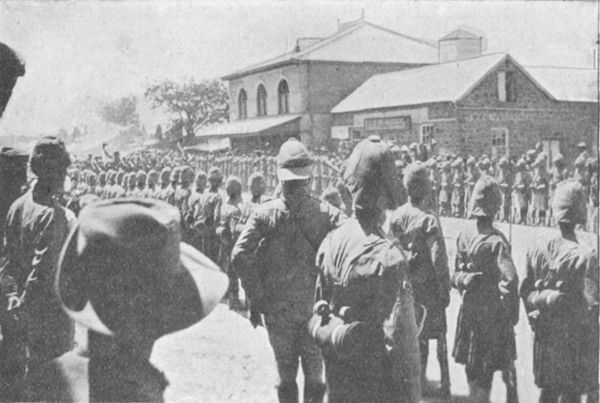

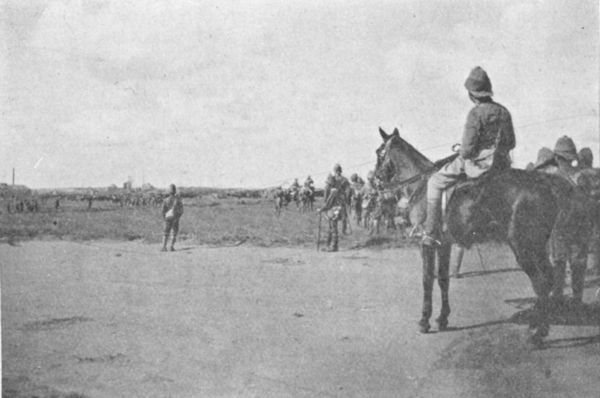

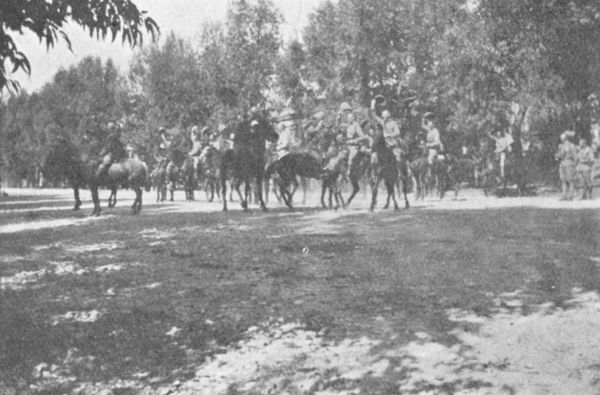

- 2ND ROYAL, DUBLIN FUSILIERS, HEADING RELIEF TROOPS, MARCHING INTO LADYSMITH, MARCH, 1900,

- GENERAL SIR REDVERS BULLER, V.C., ENTERING LADYSMITH

- THE DUBLINS ARE COMING—LADYSMITH

- SIR GEORGE WHITE WATCHING RELIEF FORCE ENTERING LADYSMITH

- SERGEANT DAVIS IN MEDITATION OVER ‘LONG CECIL’ AT KIMBERLEY. ‘SHALL I TAKE IT FOR THE OFFICERS?’

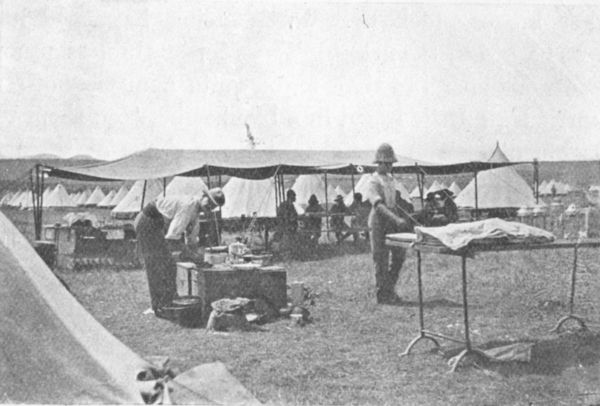

- ST. PATRICK’S DAY IN CAMP. PRIVATE MONAGHAN, THE REGIMENTAL BUTCHER, IN FOREGROUND

- A WASH IN HOT WATER—ALIWAL NORTH

- THE REGIMENTAL MAXIM IN ACTION AT FOURTEEN STREAMS

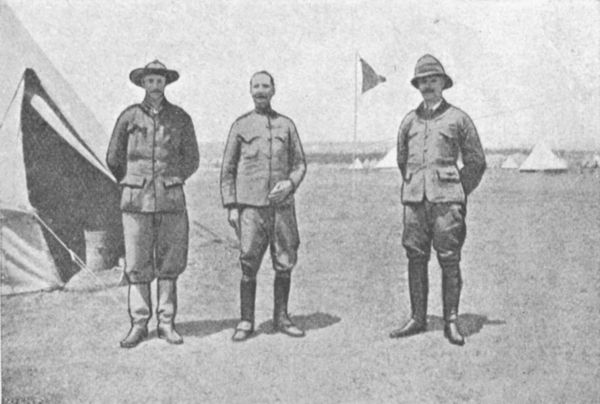

- CAPTAIN JERVIS, GENERAL FITZROY HART, C.B., C.M.G., AND CAPTAIN ARTHUR HART

- ISSUING QUEEN VICTORIA’S CHOCOLATE. COLOUR-SERGEANT CONNELL, ‘G’ COMPANY, ON LEFT

- FIRST ENTRY INTO KRUGERSDORP. CAPTAIN AND ADJUTANT FETHERSTONHAUGH IN FOREGROUND

- ‘SPEED, DEAD SLOW’

- HOISTING THE UNION JACK AT KRUGERSDORP

- JOHAN MEYER’S HOUSE, FIVE MILES OUTSIDE JOHANNESBURG

- SERGEANT DAVIS, EVIDENTLY WITH ALL WE WANTED

- PAARDEKRAAL MONUMENT, KRUGERSDORP

- THE OFFICERS’ MESS

- CORPORAL TIERNEY AND CHEF BURST

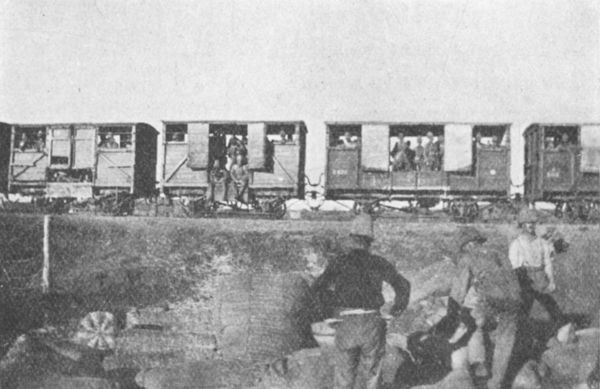

- FOURTH CLASS ON THE Z.A.S.M.

- FIFTH CLASS ON THE Z.A.S.M.

- THE VAAL RIVER, LINDEQUE DRIFT

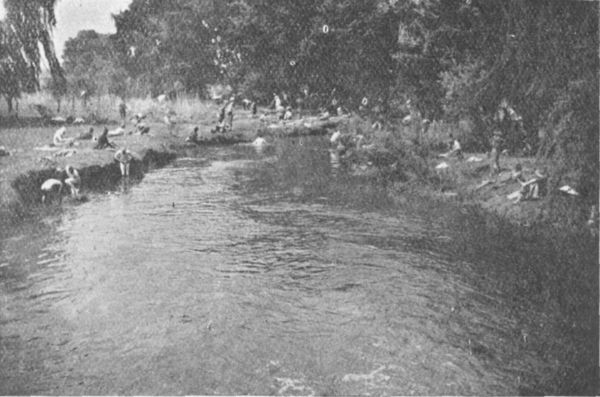

- THE R.D.F. BATHING IN MOOI RIVER, POTCHEFSTROOM

- FATHER MATHEWS

- FUNERAL OF COMMANDANT THERON AND A BRITISH SOLDIER, SEPT. 6TH, 1900

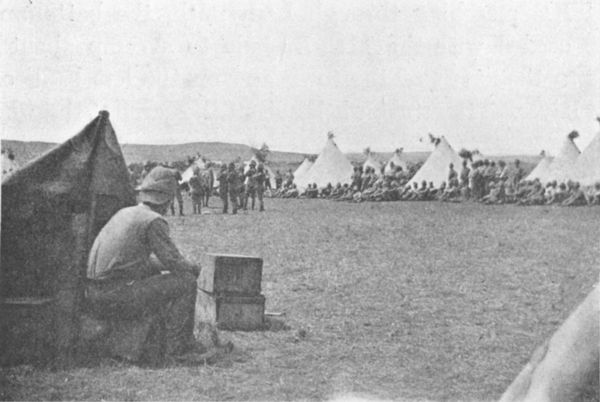

- BUFFELSDOORN CAMP, GATSRAND HILLS

- A GROUP OF BOER PRISONERS TAKEN AT THE SURPRISE OF POCHEFSTROOM

- COLOUR-SERGEANT COSSY ISSUING BEER

- ‘COME TO THE COOK-HOUSE DOOR, BOYS!’

- SERGEANT FRENCH AND THE OFFICERS’ MESS, NACHTMAAL

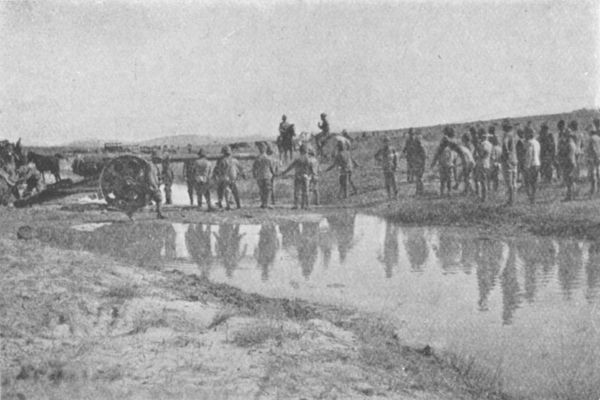

- 4·7 CROSSING A DRIFT, ASSISTED BY THE DUBLIN FUSILIERS

- BOY FITZPATRICK WAITING AT LUNCH

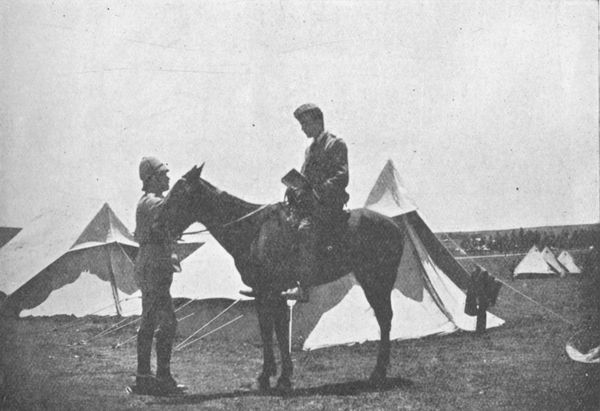

- ‘THE LATEST SHAVE.’ CAPTAIN G. S. HIGGINSON (MOUNTED) AND MAJOR BIRD

- THE HAIRDRESSER’S SHOP

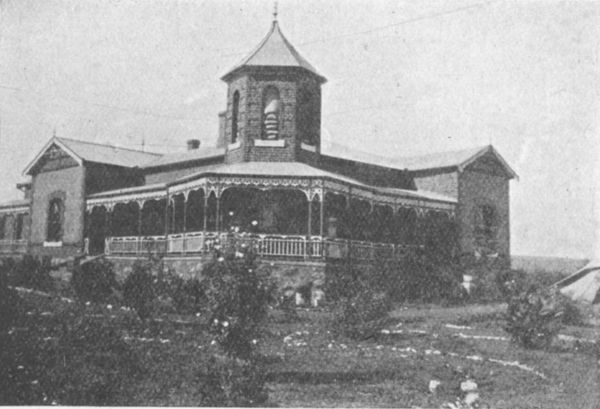

- KILMARNOCK, KRUGERSDORP

- A BLOCKHOUSE

- THE ‘BLUE CAPS’ RELIEVING THE ‘OLD TOUGHS’

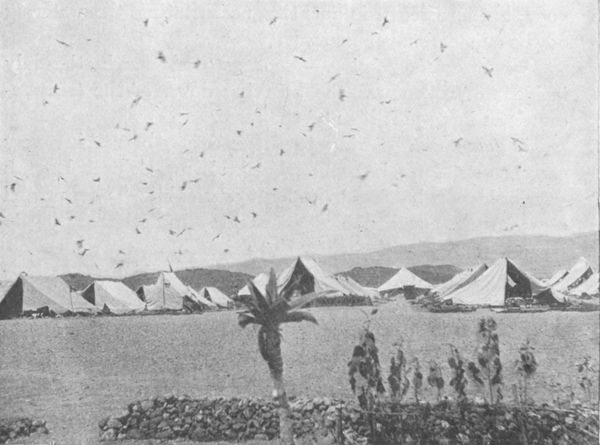

- DTHALA CAMP

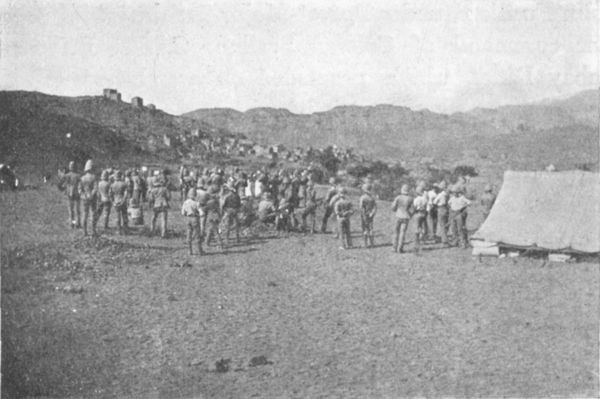

- DTHALA VILLAGE, FROM CAMP

- A FRONTIER TOWER—ABDALI COUNTRY

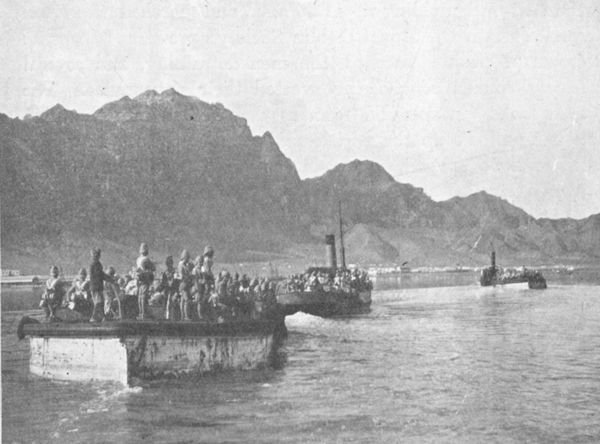

- HOMEWARD BOUND AT LAST, AFTER TWENTY YEARS’ FOREIGN SERVICE

PART I.

FIGHTING.

THE 2ND BATTALION

ROYAL DUBLIN FUSILIERS

CHAPTER I.

TALANA.

‘The midnight brought the signal sound of strife,

The morn the marshalling in arms, the day—

Battle’s magnificently stern array.’

Byron.

The 2nd Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers left India for Maritzburg, Natal, in 1897, and therefore, on the outbreak of the war between Great Britain and the South African Republics, had the advantage of possessing some acquaintance with the topography of the colony, and of a two years’ training and preparation for the long struggle which was to ensue.

The political situation had become so threatening by July, 1899, that the military authorities began to take precautionary measures, and the battalion was ordered to effect a partial mobilisation and to collect its transport. On September 20th it moved by train to Ladysmith,[1] and four days later proceeded to Dundee. Here Major-General Sir W. Penn-Symons assumed the command of a small force, consisting of 18th Hussars, 13th, 67th, and 69th Batteries R.F.A., 1st Leicestershire Regiment, 1st King’s Royal Rifles, and 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers. Each infantry battalion had a mounted infantry company. The brigade was reinforced on October 16th by the 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers.

The country was still nominally at peace, but the Dundee force held itself ready for emergencies, and sent out mounted patrols by day and infantry piquets by night, while the important railway junction at Glencoe was held by a company. The General utilised this period of waiting in carrying out field-firing and practising various forms of attack. As he was a practical and experienced soldier, he succeeded in bringing his command to a high state of efficiency, and the battalion owed much to his careful preparation. It was due largely to his teaching that the men knew how to advance from cover to cover and displayed such ready ‘initiative’ in the various battles of the Natal Campaign. The opportunity of putting into practice this teaching soon presented itself, for on October 12th news was received that the South African Republics had declared war on the previous day.

Consideration of the advisability of pushing forward a small force to Dundee, and of the reasons for such a movement, does not fall within the scope of this work; but a glance at the map will show that Sir W. Penn-Symons had a wide front to watch, since he could be attacked from three sides. Although precise information regarding the Boer forces was lacking, it was known that commandoes were assembling at Volksrust, along the left bank of the Buffalo River, and on the far side of Van Reenan’s Pass.

Early in the morning of October 13th a telegram was received from Sir G. White, asking General Penn-Symons to send a battalion to Ladysmith at once, as the Boers were reported to be advancing on that town. The General paid the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers the compliment of selecting them for this duty, and they entrained accordingly, about 4.30 a.m., reaching Ladysmith some four hours later. They detrained with the utmost haste and marched at once towards Dewdrop, whither the Ladysmith garrison had been sent; but the report of a Boer advance was discovered to be without foundation, and the battalion was halted five miles outside Ladysmith, and ordered to return. It did not reach the camp at Dundee until 11 p.m.

On the following day Sir W. Penn-Symons moved his detachment closer to the town of Dundee, and placed his camp three or four hundred yards north of the road to Glencoe Junction. It soon became clear that the Boers meant to invade Natal, and Newcastle was occupied by them on the 15th, while the mounted patrols of the Dundee force were already in touch with the commandoes on the left bank of the Buffalo. The detached company at Glencoe was withdrawn on the 18th, and on the 19th three companies of the regiment, under Major English, were sent to the Navigation Colliery in order to bring away large quantities of mealie bags stored there.

Colonel Cooper, commanding the 2nd Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers, had been given an extension of his command, and was hurrying back from a short period of leave in England, so the battalion was at this time under the command of Major S. G. Bird.

It was now evident to every one that we were on the eve of hostilities, and a spirit of keen excitement and anticipation ran through all ranks. After a long tour of foreign service, during which the regiment had not had the good fortune to see active service, though on three occasions they had been within measurable distance of it, they were now to have the long-wished-for chance of showing that, in spite of altered denominations and other changes, they were prepared to keep their gallant and historical reputation untarnished. Our advanced patrols had already seen the first signs of the coming torrent of invasion, and one and all were seized with that feeling, common to all mankind, of longing to get the waiting and the preparation over, and to commence the real business for which they had been so carefully and so thoroughly prepared. Full of the most implicit confidence in their brave leader, the regiment knew to a man that they would soon be at hand-grips, and their two years’ residence in the country and knowledge of the history of the last Boer War, and the stain to be rubbed out, made every pulse tingle with the desire to show that the past had been but an unfortunate blunder, and that the British soldier of the present day was no whit inferior to his predecessors of Indian, Peninsular, Waterloo, and Crimean fame.

On the night of the 19-20th October, Lieutenant Grimshaw was sent with a patrol of the Mounted Infantry company of the battalion to watch the road to Vant’s and Landsman’s Drifts, ten miles east of Dundee. About 2 a.m. on October 20th this officer reported that a Boer commando was advancing on the town. At a later hour he forwarded a second message to the effect that he was retiring before superior numbers, one man of his party having been wounded, and that the enemy were in occupation of the hills to the east of the town. On the receipt of this message General Penn-Symons ordered two companies of the Dublin Fusiliers to support Lieutenant Grimshaw. ‘B’ and ‘E’ companies, under Captains Dibley and Weldon, accordingly left camp at 4 a.m., and, moving through the town, took up a position in Sand Spruit, which runs along the eastern edge of Dundee. The whole brigade stood to arms, as usual, at 5 a.m., but was dismissed at 5.15 a.m. At about 5.30 a.m. the mist lifted, and everybody’s gaze was directed on Talana Hill, where numbers of men in black mackintoshes could be seen. The general impression was that they were members of the town guard, but the arrival of the first shell soon dispelled this illusion.

Soon after 5.30 a.m. the Boer artillery opened fire on the camp. Their fire was accurate enough, considering that the range was near 5400 yards, but the damage done was practically nothing, as very few shells burst, and these only on impact. Our own artillery (13th and 69th Field Batteries, with ‘D’ company of the battalion as escort) did not immediately respond, as they were at the time engaged in watering their horses; but as soon as possible they were in position to the east of the camp, and began to shell the crest of Talana Hill. They obtained the range almost immediately, and in a short time overpowered the hostile guns, which were thus prevented from playing an important part in the day’s battle.

As soon as the Boers started shelling the camp, the battalion fell in on its parade-ground in quarter-column and waited for orders. But when a shell fell just behind the ranks, Major Bird moved it at the double through the camp to a donga which afforded good cover. The men then removed their great-coats, and stayed for some minutes watching the Boer shells passing over their heads. Eventually the King’s Royal Rifles, Royal Irish Fusiliers, and the battalion were ordered by the General to move in extended order through the town, and to concentrate in the spruit already occupied by ‘B’ and ‘E’ companies. The Leicesters and 67th Battery were left near the camp to watch Impati Mountain, since it was probable that the Boer force which had occupied Newcastle would appear from that direction. The mounted troops (18th Hussars and the Mounted Infantry company of the Dublin Fusiliers, under Captain Lonsdale, less Lieutenant Cory’s section, which, fortunately for it, was sent off in another direction), under the command of Colonel Möller, were sent to turn the right flank of the Boers’ position on Talana Hill and so threaten their rear.

As the extended lines of the infantry moved through the town they were greeted by pompom fire, which, however, did no damage. It was their first introduction to this hated and under-rated weapon, whose moral effect is so great that, even if the casualties it inflicts are small in number, it is always likely to exercise a marked influence, more especially on young troops and at the commencement of a campaign. Men heard it in wonder, asking each other what it was, and why had we nothing like it, and similar questions. By 6.30 a.m. the three battalions were assembled in the bed of the spruit, and the General rode up with the Staff in order to give his orders for the attack. The 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers were to form the firing line, with the 60th Rifles in support and the Royal Irish Fusiliers in reserve. Under Talana Hill is a wood surrounding a small house known as Smith’s Farm. Between this wood and Sand Spruit is a long stretch of veld, which on the day of the battle was intersected by several wire fences. The battalion received orders to cross this open ground by successive companies, ‘H’ company, under Lieutenant Shewan, formed the right of the line, and was the first company to leave the shelter of the spruit. It made for the south-east corner of the wood, where it was afterwards joined by the maxims, and at once opened fire on Talana and Dundee Hills. ‘B’ company under Captain Dibley, ‘A’ company under Major English, and ‘E’ company under Captain Weldon extended to ten paces, and followed in succession. The enemy had by this time developed a vigorous fire, but the range was long and the casualties small. The advancing companies moved on steadily, reached the edge of the wood, and entered it. They now became somewhat separated. ‘A,’ ‘G’ (Captain Perreau), and ‘F’ inclined to the left, ‘C’ and ‘E’ remained in the centre with ‘B’ on their right, while ‘H’ was held back at the corner of the wood. The latter was bounded on the far side by a stone wall, beyond which stretched an open piece of ground until, further up the hill, there was a second wall. At this point there was a sudden change in the slope of the ground, which rose almost precipitously to the crest. Immediately opposite the point where ‘B’ company issued from the wood a third wall ran up the hill, connecting the two already mentioned. When the attackers reached the far end of the wood, they came under such a well-directed and heavy fire that their progress was at first checked, in spite of the support afforded by our artillery, which rained shrapnel on the hostile position. The Boers, lying behind the boulders on the crest of Talana Hill, found excellent cover; while from Dundee Hill they could bring an effective enfilade fire on the open space between the two parallel walls. Opposite ‘A’ company a donga ran up the hill, and at first sight seemed to offer an excellent line of approach for an attacking force. Major English, in command of the company, rushed forward and, in spite of a heavy fire, succeeded in cutting a wire fence which closed the mouth of the donga. He then, at about 8 a.m., led his company into the latter, and was followed by ‘G’ and ‘F’ (Captain Hensley) companies; but the donga proved almost a death-trap, since it was swept by the rifles of some picked marksmen on the right of the Boer position.

Capt. G. A. Weldon.

Killed.

Second Lieut. Genge.

Died of Wounds.

Capt. A. Dibley.

Wounded.

Major Lowndes.

Wounded.

Lieut. C. N. Perreau.

Wounded.

Ser.-Maj. (now Qr.-mr) Burke.

Wounded.

Casualties at Talana.

It was impossible for these three companies to advance any further, and they were therefore forced to limit their efforts to an attempt to keep down the Boer fire. Meanwhile, General Penn-Symons had, about 9.15 a.m., come up to the far edge of the wood, and crying, ‘Dublin Fusiliers, we must take the hill!’ crossed the wall. Shortly afterwards he received a mortal wound. Captain Weldon was also killed near the same spot in a gallant effort to help a wounded comrade, No. 5078 Private Gorman. Captain Weldon, together with several men of his company, had surmounted the wall in face of a heavy fire, and had taken cover in a small depression on its further side. Private Gorman was hit in the very act of surmounting the obstacle, and was falling backwards, when Captain Weldon, rushing out from his cover, seized him by the arm, and was pulling him into safety when he himself was mortally wounded. Privates Brady and Smith dragged him in under cover, but he only lived a few minutes. His dog, a fox-terrier named Rose, had accompanied him through the fight, and when his body was later on recovered, the faithful little animal was found beside it, and was afterwards taken care of by the men of ‘E’ company. There was no more popular officer in the regiment than George Weldon, and his loss was deeply felt by all ranks. He was the first officer of the Dublin Fusiliers to fall in the war, which thus early asserted its claim to seize the best. He was buried that same afternoon in the small cemetery, facing the hill on which he had met his death.

The Last Rites.

By this time, 9.30 a.m., the Rifles and Irish Fusiliers had closed up and become merged in the firing line. Slowly, and by the advances of small parties at a time, the attackers gained ground, principally by creeping along the transverse wall which afforded cover from the enemy on Dundee Hill, Helped by the incessant fire of the artillery, which at 11.30 a.m. moved up to the coalfields railway, the infantry gradually collected behind the second wall. They were now within 150 yards of the crest, and the roar of battle grew in intensity. About 11.30 a.m. Colonel Yule came up and ordered the hill to be assaulted, directing the battalion to charge the right flank of the hill, and the Rifles the centre. Captain Lowndes, who was with the companies on the right, led them across the wall and over an open piece of ground. He gave the command ‘Right incline,’ and so well were the men in hand that the order was promptly obeyed, shortly after which he was badly wounded. Meanwhile, in the centre, men of all three regiments, led by the Staff and regimental officers, dashed over the wall and began to clamber up the steep and rocky slope. The artillery quickened its fire and covered the crest with shrapnel. But the Boers still remained firm. Many of them stood up, their mackintoshes waving in the wind, and poured a deadly fire on the assaulting infantry. Though most of these brave burghers paid for their daring with their lives, they repulsed this first gallant charge. The Dublin Fusiliers suffered many casualties in this first assault. Captain Lowndes, the Adjutant, had his leg practically shattered, as he, with the other officers, ran ahead to lead the charge. Captain Perreau was shot through the chest; Captain Dibley was almost on the top of the hill when hit. He had a dim recollection of the gallant Adjutant of the Royal Irish Fusiliers racing up almost alongside him and within a few paces of the summit, when he suddenly saw an aged and grey-bearded burgher drawing a bead upon him at a distance of a few paces only. He snapped his revolver at him, but only to fall senseless next moment with a bullet through his head. Marvellous though it seems he made a comparatively speedy recovery, and was able to ride into Ladysmith, at the head of his company, in the following February, having been in the hospital in the besieged town in the interval. Evidence of the temporary nature of the discomfort caused by a bullet through the head is afforded by the fact that he is to-day one of the best bridge-players in the regiment. Poor young Genge, who had only recently joined, was mortally wounded, and died shortly after the battle, killed in his first fight and in the springtime of life.

Sergeant-Major Burke’s (now Quartermaster) experiences may be best told in his own words: ‘It must have been shortly after poor Weldon was killed that I came across “E” company; finding no officer with them I assumed command, and on arrival at the donga handed them over to Major Bird, and accompanied Colonel Yule, who had just arrived, and was ascending the hill. We had only gone a few yards, and were about six paces from the top wall, when I was bowled over, hit in the leg. It was a hot place, for as I lay there another bullet hit me in the shoulder. I crawled as well as I could to a rock, and sitting up underneath it lit a pipe. Scarcely had I got it to draw when a bullet dashed it out of my hand, taking a small piece of the top of my thumb with it. Two men were shot dead so close that they fell across my legs, effectually pinning me to the ground, while two more were wounded and fell alongside of me. At this juncture Colour-Sergeants Guilfoyle (now Sergeant-Major) and James dashed out of cover, and, picking me up, carried me to a more sheltered position, whence I could see what was going on all round, without myself being seen.’ He was left at Dundee with the wounded, and subsequently taken to Pretoria with other prisoners of war.

Whilst the men and officers were thus recovering their breath for a renewed attack, a large number were undoubtedly hit by our own shrapnel, as they clung closely to the hillside to avoid coming under fire from the enemy, who still held the top. It was imperative to draw our gunners’ attention to their situation, to effect which purpose, an intrepid signaller, Private Flynn, Royal Dublin Fusiliers, jumped up, and at the imminent risk of his own life freely exposed himself in his endeavour to ‘call up’ the guns. Finding, after repeated attempts, that he could not attract their attention, he boldly walked back down the hillside, torn as it was by mauser fire, and personally delivered his message, a glorious and courageous example of that devotion to duty which proved so strongly marked a characteristic of our N.C.O.’s and privates throughout the war.

Major English now extricated his company from the donga and managed to reach the second wall, where he collected all available men, including ‘F’ and ‘G’ companies, and maintained an incessant fire on Dundee and Talana Hills. The artillery behind had never slackened in their efforts to support the infantry, and their shrapnel searched the whole length of the crest line. This combined fire began at last to tell. The rattle of the enemy’s musketry, which had lasted since 6.30 a.m., gradually grew feebler, until about 1 p.m. our infantry made a second dash across the wall and this time reached the top of the hill. Below them they saw the stream of flying Boers hurrying across the veld. It was the moment for a vigorous outburst of musketry, but ‘some one blundered,’ and the fleeting moment sped without being taken advantage of. It is true that those men who first arrived on the summit were firing away, and were joined in doing so by every other man who breathlessly arrived. The company officers had just got their men well in hand, and were directing the fire, when to every one’s disgust, and sheer, blank amazement, the ‘Cease fire’ sounded clear above the din of the fight. There was nothing for it but to stop, but the sight of the enemy streaming away in dense masses just below them, that enemy who had up to now been pouring a relentless hail of bullets on them for hours, was too much. Captain Hensley rushed up to Major English, and after a brief conference, feeling certain the call must have been blown in error, the latter gave the command to re-open fire. Barely was it obeyed when the imperative bugle once more blared forth its interference, and the company officers, the commanders of the recognised battle-units, had nothing left them but compliance.

The guns with ‘D’ company as escort had come to the neck between Talana and Dundee Hills, but did not fire. The fight was over and Major English formed up the battalion. It then marched back as a rearguard to the brigade, through Dundee to the camp, much as if after a field-day, halting half-way to receive an issue of rations sent out by the A.S.C. It had lost two officers and six men killed, and three officers and fifty-two men wounded. As the troops passed through the town they were warmly cheered by the inhabitants. Late in the afternoon news reached the camp that the Mounted Infantry company, together with a squadron of the 18th Hussars, had been captured, but this was kept from the rank and file of the battalion. As already stated above, Colonel Möller had been sent with the mounted troops round the right flank of the Boers. He succeeded in his task, but proceeded too far, and when the enemy retreated from Talana Hill he found himself with some 200 rifles attempting to stop a force of 4000 Boers. He was roughly handled, but managed to get clear. Then, unluckily misled by the mist, he lost his way, and, instead of returning to camp, moved towards Impati Mountain, where he stumbled into the Boer main commando advancing from Newcastle. He took up a defensive position, placing the cavalry in a kraal and the mounted infantry on some rising ground near. The enemy brought up artillery and soon surrounded him, finally forcing him to surrender.

Talana Hill, in point of numbers, may not rank as a great battle, but its moral effect can scarcely be exaggerated. It was the first conflict of the war. It was Majuba reversed, and the issue had far-reaching consequences. The news of the victory spread quickly through South Africa, and had considerable influence on the Dutch Colonists, who were, to use an expressive colloquialism, ‘sitting on the fence,’ and kept them sitting there, at a time when had they descended on the wrong side their action could not have failed to be extremely prejudicial to the interests of the Empire; but over and above all else it showed to the world that the British infantry could still attack and carry a position in face of modern rifle-fire, a lesson which was never forgotten by Boer or Briton, in spite of after events. Moreover, Talana must ever be a memorable name in the annals of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, since it was the first battle in which they had fought under their new title, which was from that day on to become as well known as that of any regiment in the army.

The other regiments engaged had also suffered very severely, the 60th Rifles losing, amongst other officers, their gallant chief, Colonel Gunning. It was curious that on the last occasion the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers had seen active service—the siege and capture of Mooltan—they should then have fought alongside the 60th, as they did in the present instance.

CHAPTER II.

THE RETREAT FROM DUNDEE.

‘I am ready to halt.’—Ps. xxxviii. 17.

On the morning of October 21st, Colonel Yule, who, as senior officer, had taken over command of the brigade, received the news that a Boer commando, under General Joubert, was advancing by the Newcastle road. As the camp was within long-range artillery fire from Impati Mountain, the brigade moved off at a moment’s notice to the south and took up a defensive position. The tents were left standing, but each man carried a waterproof sheet, a blanket, and great-coat, while the waggons, massed in rear, had three to four days’ supplies. Soon after 4:30 p.m. the enemy appeared on Impati, and at once opened fire with a big gun, probably a forty-pounder. The shells at first fell in the vacated camp, but the Boer artillerymen quickly discovered the brigade, and made good practice, although they caused but slight damage. Our batteries attempted to reply, but were outranged, their shells falling far short. Luckily for us a mist came on, and the Boer gun ceased firing.

As soon as night fell the troops began to entrench themselves, for the situation of the brigade was sufficiently unpleasant. In front was an enemy with superior numbers and heavier artillery, and in rear, between Dundee and Ladysmith, another hostile force of unknown strength. To make matters worse, it rained persistently and the night was cold. About 3 a.m. the brigade retreated to Indumana Kopje, some one and a half miles to the south-east of the camp. Here a new position was taken up before dawn, the guns and transport being massed behind the hill in order to be out of sight from Impati.

Early in the morning of the 22nd, the spirits of the small force were raised by the news of the victory at Elandslaagte. This caused great delight among the men: they were proud of their own victory at Talana, and this further success roused them to a still higher pitch of enthusiasm. The strategic side of the situation seldom appeals to the rank and file, and the consequence was that when the retreat was commenced they were under the impression that they were being led to yet another victory. When they were undeceived, they were undoubtedly very savage, especially so at, what seemed to them, the callous desertion of their wounded comrades in Dundee.

Since it was possible that some of the defeated Boers might be retreating through the Biggarsberg, a demonstration towards Glencoe Junction was ordered, the troops detailed being the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers, the 60th Rifles, one battery, and some cavalry. No time was given for breakfasts, but the detachment moved off at 8 a.m. with the battalion as advance guard. On arriving within 1500 yards of the Junction, the battery shelled a party of the enemy on a hill to the west of the railway, a proceeding which promptly provoked an answer from the Boer gun on Impati, but another timely mist and rain saved the detachment from this unwelcome attention. No Boers were seen in the pass, so the force, with the battalion as rearguard, returned to Indumana Kopje at 12.30 p.m., when they were able to obtain dinners, the majority of the men having been without food for twenty-four hours.

At 9 p.m. that evening orders were issued for the reoccupation of Talana Hill by the whole force, but the various commanding officers were informed confidentially that Colonel Yule’s real intention was a retreat to Ladysmith by the Helpmakaar road. It was an extremely dark night, and the battalion occupied nearly two hours in collecting the companies and reaching the place of assembly at the foot of the kopje. It was not until after 11 p.m. that the brigade actually started on the retreat in the following order: 1st 60th Rifles (advance-guard), 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers, 13th Battery, Mounted Infantry, Transport, 67th and 69th Batteries, 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers, 18th Hussars, 1st Leicestershire Regiment (rearguard). The force occupied about four miles of road. The route was through Dundee, over Sand Spruit, and down the Helpmakaar road through the Coalfields village. It was impossible to find an opportunity for a return to the camp, which was left standing. All the tents, stores, and baggage, together with the wounded, were left to the enemy. The battalion thus lost its band instruments and camp equipment, while the officers had to sacrifice all their personal kit, and many articles belonging to the mess. The waggons carried nothing but supplies, and no one in the force was able to take away anything beyond what he carried on his person.

Armourer-Sergeant Waite.

‘Delenda Est Carthago.’

The column marched throughout the night, and far into the morning of the 23rd, only halting at 10 a.m., when dinners were eaten on the high ground south of Blesbok Pass, about fifteen miles from Dundee. That the Boers were watching the retreat was proved by one of their heliographs trying to ‘pick up’ the column. The march was resumed after a two hours’ rest, and continued to Beith (twenty-one miles from Dundee), where, at 3 p.m., another halt was made. The men cooked their teas, and had a chance of a brief sleep, but at 11 p.m. they had to start again. The road, a very bad one, lay through the pass leading to the Waschbank River. The battalion formed the advance-guard, with two Natal mounted policemen as guides. It was a weary tramp, for, owing to the wretched road, long halts were necessary in order to allow the waggons to close up. At dawn, the 18th Hussars took over the duties of advance-guard, and were supported by ‘F’ company, under Captain Hensley.

During the night a mysterious heliograph was seen twinkling and blinking away on the left flank. After some difficulty it was ascertained that it was communicating with the farm of a man named Potgieter, professedly a British subject. He was, in fact, caught in flagrante delicto in full communication with the unknown Boer signaller, and paid for his crime with his life.

At 10 a.m. on the 24th, the head of the column reached the Waschbank (thirty-six miles), crossed, and halted on the south side of the river. The waggons were not over until 12.30 p.m. A welcome meal and a bathe in the stream refreshed the men, some of whom had had no proper sleep for three nights. Heavy firing was heard from the direction of Ladysmith, and the mounted troops, with the artillery, were sent off to reconnoitre and see if they could render any assistance to Sir George White. They met with nothing, however, and returned before 5 p.m. Meanwhile the infantry had also been disturbed, for at 2 p.m. they recrossed the river in order to occupy a better position to oppose a rumoured pursuit of the Boers. As the latter did not appear, the river was again forded at 4 p.m., and only just in time. A violent thunderstorm burst, and the water rose ten feet in two hours. ‘H’ company, under Lieutenant Shewan, and a patrol of the 18th Hussars were left on the north bank, and were thus cut off from the main body for several hours.

It rained in torrents until 11 p.m., and the battalion, formed in quarter-column, had to lie down in pools of water, and get what sleep it could. At 5 a.m. on the 25th, in bright sunshine, the retreat was resumed. ‘H’ company crossed to the south bank a few minutes before the column moved off, although the water was still up to the men’s waists. The Dublin Fusiliers formed the rearguard, and marched till mid-day, when Sunday’s River (forty-eight miles) was reached. ‘A’ company remained on the north bank to cover the crossing of the waggons, and at 2.30 p.m. the column went on, only halting at 4.30 for tea. Everybody hoped to have a long rest here, but at 6.30 p.m. Major Bird was sent for, and informed that, as the Boers were in close pursuit, a night march was necessary.

The brigade accordingly started at 7 p.m., at the same moment that heavy rain began to fall. The road quickly became inches deep in mud, every one was soon wet to the skin, and the night was so dark that a man in each section of fours had to hold on to the canteen strap of the man in front in order to keep the proper direction. As an additional evil, the battalion was still rearguard, which is generally the most tiring position in a column. Halts were frequent, and the men were so exhausted that many of them, when they stopped for a moment, fell down in the mud and slept. Soon after midnight the 18th Hussars, who were keeping connection between the Irish Fusiliers and the rearguard, disappeared. It was so dark that the latter could have no certainty of being on the right road, but was obliged to struggle on blindly. Majors Bird and English established a code of signals by whistle, in order to keep the companies closed up. Dawn still found the battalion marching, dead tired, but luckily in its proper place behind the column, and without a man missing. It was not until 8 a.m. on the 26th that this wearisome march ended. Then Modderspruit, seven miles north of Ladysmith, and sixty-five from Dundee, was reached, and the men sank down, too weary to care about anything. After a brief interval, however, they recovered sufficiently to eat their bully beef and biscuits. It had been a trying march for all, although the column had accomplished only twelve miles in eleven hours. As an instance of the general weariness, it is recorded that a subaltern, during the meal, was asked to pass the mustard, and fell asleep with his arm outstretched and the mustard-pot in his hand.

But the brigade was still not allowed to rest. At 11 a.m. it was on the ‘trek’ again, and marched till 2 p.m., when the long retreat came to an end, and Ladysmith was entered. Here the Devonshire and Gloucestershire Regiments earned the undying gratitude of the regiment by providing officers and men with a meal, as well as by pitching a camp for them.

On arriving at Ladysmith, tents, equipment, mules, and, in fact, all that had been lost at Dundee, were issued, and the battalion went into camp near the cemetery.

The column was fortunate in having Colonel (now General) Dartnell with it. This officer, after serving with distinction for many years in the regular army, had, on retirement, settled down in Natal, where he was, previous to the war, in command of the Natal Police. A great hunter and fisherman, he knew every inch of the country, knowledge which proved of invaluable assistance in the trying march.

CHAPTER III.

FROM COLENSO TO ESTCOURT.

‘If thou hope to please all, thy hopes are vaine;

If thou feare to displease some, thy feares are idle.’

Francis Quarles.

On October 28th Colonel Cooper arrived at Ladysmith from England and took over the command from Major Bird. The battalion was able to rest from the 27th to the 29th, and recover from the fatigue of the retreat to Ladysmith.

The Headquarter Staff issued orders on the 29th for a general movement, to take place the next day, against the enemy, who were closing in on the town. The Dublin Fusiliers formed part of Colonel Grimwood’s brigade, which also included the 1st and 2nd King’s Royal Rifles, the Leicesters, and the Liverpools. The task assigned to Colonel Grimwood was the capture of Long Hill.

In order to be in position for the assault by dawn, it was necessary for the brigade to make a night march, and the battalion paraded about 9.30 p.m. on Sunday evening, the 29th October. It formed the rear of the brigade, to which was attached a brigade of artillery. ‘F’ and ‘B’ companies were left behind on piquet duty.

Owing to the difficulties inherent in a night march, and, perhaps, also to faulty staff management, the artillery, the Dublin Fusiliers, and Liverpool Regiment diverged from the route followed by the rest of the brigade. As a result of this mistake the battalion took practically no part in the battle of the 30th, but, after a vain endeavour to find Colonel Grim wood’s force, spent the morning lying on the crest of a small ridge near Lombard’s Kop. It came under shell and long-range rifle fire, but lost no men. The attempt to drive back the Boers was a failure, and the army fell back on Ladysmith about mid-day. The battalion reached camp at 2 p.m. and was dismissed. All ranks were somewhat tired, for the sun had been hot, and after dinner sleep reigned supreme.

Railway Bridge at Colenso.

But about 4 p.m. Colonel Cooper received from Headquarters an order to proceed by train to Colenso, with the object of protecting the important railway bridge which crosses the Tugela at that place. The Natal Field Artillery, in addition to his own unit, was placed under his command. On the receipt of this order, camp was struck, and the tents and baggage sent down to the station. The piquets found by the Dublin Fusiliers were ordered to be relieved by other corps, but although ‘F’ company, under Captain Hensley, came in, Lieutenant H. W. Higginson’s piquet, on the ridge to the east of the cemetery, could not rejoin in time, principally owing to the fact that the greater part of the Gloucestershire Regiment, which had been detailed to find the relief, had been captured at Nicholson’s Nek. Lieutenant Higginson and his men were thus left to share in the siege of Ladysmith. The battalion transport, under Lieutenant Renny, also had to remain behind. An account of their experiences during the siege is given by Lieutenant Renny in Chapter IX.

With these exceptions the whole battalion marched down to the station soon after 11 p.m., and was dispatched in two trains. As Boers had been reported on Bulwana Hill during the afternoon, a certain amount of risk seemed to attend the journey. There was nothing to prevent the enemy from cutting the line at any point in the hilly country between Ladysmith and Pieter’s Station, while even a small hostile force could have played havoc with the crowded trucks.

However, the enemy had luckily not penetrated to the railway line, and after an uneventful, though unpleasant, journey, Colenso was reached at 4.30 a.m. on the 31st.

The two railway bridges over the Tugela and Onderbrook Spruit were already protected by a small force, consisting of the Durban Light Infantry, a squadron of the Imperial Light Horse, and a detachment of the Natal Naval Volunteers, with a gun. These units had made good defensive works, notably Forts Wylie and Molyneux, guarding the railway bridges over the Tugela and Onderbrook Spruit respectively.

We encamped some 300 yards south-west of Colenso, and the day (October 31st) was spent in making further defences, and dividing the garrison into sections. Colenso was not, however, an easy place to defend. It was commanded by the lofty hills on the left bank of the Tugela, and by Hlangwane Hill on the right bank to the east of the village. The garrison, moreover, was lacking in artillery, having only some muzzle-loading guns with a very limited range. Colonel Cooper telegraphed to Maritzburg asking for a naval twelve-pounder, which, however, could not be obtained.

Major-General C. D. Cooper, C.B.

Commanding 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers in Natal.

The necessity for such an addition soon arose. At 8.15 a.m. on November 1st, the staff at Ladysmith sent a wire to say that a Boer force had moved at daybreak towards Colenso. On receipt of this news the garrison was warned to be ready, and patrols of the Imperial Light Horse and the Mounted Infantry section of the battalion were dispatched towards Ladysmith, Springfield, and the country beyond Hlangwane. These patrols returned soon after 1 p.m., and the party which had reconnoitred towards Ladysmith reported that it had come into touch and exchanged shots with the enemy. Later on in the afternoon, Lieutenant Cory, commanding the Mounted Infantry section, went out again and reported that he had seen a hostile force, estimated at 2000 men, which was off-saddled near the main Ladysmith road, some six miles out. He had skirmished with the scouts of this commando and had lost one man. Another wire came from Ladysmith at the same time announcing that the enemy had guns. Our piquets were, in consequence of these events, pushed forward to the horseshoe ridge on the left bank of the Tugela, while the parties guarding the two bridges (road and railway) over this river were reinforced. The night, however, passed quietly.

Mounted patrols were sent out at dawn of the 2nd, and Lieutenant Cory was able to report, at 6.45 a.m., that the Boers were still in the same position. But two hours later he forwarded another message to the effect that the enemy was advancing on Grobelaar’s Kloof. Soon afterwards distant rifle-shots were heard, and the Mounted Infantry retired into camp. About 10 a.m. parties of the enemy appeared on the top of Grobelaar’s Mountain, and by the aid of a good telescope it could be seen that they were busily engaged in digging. Their intention was not long in doubt, for a thin cloud became visible on the sky-line, and the next moment a shell buried itself in the river-bank.

Colonel Cooper at once ordered the tents to be lowered and the trenches to be manned. But the enemy made no signs of attacking Colenso, and contented themselves by occasionally firing shells which invariably fell short. The interruption of telegraphic communication with Ladysmith soon after 3 p.m. proved, however, that the enemy was not being idle. Groups of Boers could be seen on the hills overhanging the railway, and a train carrying General French was shelled after leaving Pieters. The activity of our foes assumed a more aggressive character when, about 5 p.m., they began to bombard Fort Molyneux. From Colenso the shrapnel could be plainly seen bursting over the work, and the piquets on the left bank of the Tugela reported that heavy rifle-fire was in progress. As the garrison of the fort consisted only of eighty men of the Durban Light Infantry, some anxiety was felt regarding their safety, and this uneasiness was intensified by the arrival of one of the defenders, who announced that the redoubt was hard pressed. Lieutenant Shewan, with one hundred men mostly from ‘E’ company, was promptly dispatched to reinforce them in the armoured train. He found that the fort had been evacuated, but managed to pick up several of the garrison in spite of the enemy’s rifle and shrapnel fire. Captain Hensley, who was holding the horseshoe ridge, also advanced with ‘F’ company, and, by firing long-range volleys, helped to cover the retirement of the remainder of the garrison, the whole of which reached Colenso in the night. Colonel Cooper telegraphed an account of these events to Brigadier-General Wolfe-Murray at Maritzburg, who replied at nightfall that, since the safety of Colenso bridge was very important, he would send the Border Regiment next day to reinforce the garrison. But no mention was made of any artillery.

Colonel Cooper had now a difficult decision to arrive at. In front of him lay a superior force of the enemy with guns far outranging his own obsolete muzzle-loaders, and during the afternoon disquieting rumours, which might be true, of another commando at Springfield had reached him. Ladysmith was invested, and the small garrisons of Colenso and Estcourt alone stood between the Boers and Maritzburg. Having consulted the senior officers of the garrison, Colonel Cooper sent another wire to General Wolfe-Murray explaining the situation, and in reply was authorised to fall back to Estcourt if he could not hold Colenso. About 10 p.m. he reluctantly determined to retire.

The mounted troops and the Natal Field Artillery went by road, starting at midnight. It was decided to send the rest of the garrison by railway, and the stationmaster at Colenso, with great energy, succeeded in obtaining three trains which arrived in the early hours of November 3rd.

The operation of entraining was at once commenced. The night was dark, and the packing of all the tents, supplies, and equipment in the trucks proceeded but slowly. The Natal Naval Volunteers had to bring their nine-pounder gun down the steep slope of Fort Wylie, a task requiring great care and time; the piquets on the left bank of the river had to be withdrawn, and the two bridges guarded up to the very last moment. Although everything was done in the utmost possible silence, it yet seemed that the necessary shunting of the trains must warn the Boers of the evacuation, and bring on an attack. But there was no interruption, and the last train steamed out of Colenso station half an hour before dawn.

Estcourt was reached two hours later. The little town was already occupied by a detachment of the Imperial Light Horse and Natal Mounted Rifles. During the morning there also arrived from Maritzburg the 2nd Border Regiment,[2] afterwards to be the comrades of the battalion in the 5th Brigade.

Colonel Cooper took over the command of the garrison and immediately set to work on the arrangement of the defences. The next day, however, General Wolfe-Murray and his staff appeared on the scene. Estcourt had thus the honour of having three different commandants in two days.

CHAPTER IV.

ESTCOURT AND FRERE.

‘Great men are not always wise: neither do the aged understand judgment.’—Job, xxxii. 9.

The stay at Estcourt (November 3rd to 26th) was a period of great anxiety and hard work. That there was cause for anxiety may be easily understood when the state of affairs is remembered. The Army Corps had not yet arrived from England, nor could any fresh troops be expected before the 10th. The Boers had invaded Natal, had shut up in Ladysmith the only British army in the field, and could still afford to send five or six thousand men against Maritzburg. The Estcourt garrison alone stood in their way.

There were necessarily many outposts, and tours were long and frequent. Thunderstorms, Natal thunderstorms, visited the town with painful regularity, and rendered piquet work even more uncomfortable than usual. It was a period of strained waiting, when every one wondered whether a Boer commando or a British brigade would be the first arrival. Reliable news was scarce, though rumours of every kind were rife.

The battalion was encamped in the market square, while the officers inhabited a small room encumbered with planks. Trenches covered the town to the north and north-east, and were pushed forward some two miles on the Weenen road. The citadel, so to speak, was the sugar-loaf hill, on which Lieutenant James, R.N., constructed, towards the middle of the month, emplacements for his two naval twelve-pounders. These guns arrived on November 14th, a welcome addition to the garrison, which had been strengthened on the 13th by the West Yorkshire Regiment. These reinforcements came at an opportune moment, for the Boers had at last moved forward and on November 14th their patrols were close to Estcourt. Their approach caused a certain amount of alarm, and at first the evacuation of the town was proposed. The camp was even struck, and a great part of the baggage was put on to trains which were kept ready in the station. Later on other counsels prevailed, and tents were raised again. It had rained most of the day, and a general wetting was the chief result of this ‘scare.’ The Boers quickly made their presence felt, and the next day inflicted a severe blow on the garrison.

Our mounted troops had been busily engaged in reconnaissance work, and in an evil hour it occurred to the authorities that the armoured train was also an excellent means of gaining news. Captain Hensley had taken it to Colenso on the 5th and 6th, and on the latter day surprised a party of Boers engaged in looting the village. The dispatch of the train, unsupported by any mounted troops, soon became almost a matter of daily routine. This defiance of common sense could have only one result. On November 15th, Captain Haldane,[3] of the Gordon Highlanders, went out in the train with ‘A’ company and some men of the Durban Light Infantry. He reached Frere and, learning from a Natal policeman that the front was clear, pushed on to Chieveley. Here he saw in the distance a small body of the enemy moving southwards, and, having telegraphed the information to Estcourt, turned back. But as the train was running down a steep gradient the Boers suddenly opened fire with two guns from a ridge to the west of the line. Almost immediately afterwards the train was derailed by stones placed on the line, and the leading truck upset, thus stopping the engine.

It was a predicament trying to the nerves of even the bravest. The Boer shells were well aimed, and came in quick succession. But Captain Haldane and his men did all that could be done. Lieutenant Frankland directed from the rear truck a vigorous fire, which kept the enemy at a respectful distance, and even made them shift their gun. Meanwhile Mr. Winston Churchill, who had accompanied the expedition as a Press correspondent, collected some men and set to work to push the derailed truck off the line. They were exposed to a heavy fire, but eventually succeeded in their task. The train began to move again; luck did not, however, favour them, for the coupling between the engine and rear truck was broken by a shell. Then Captain Haldane ordered the engine to return to Estcourt with as many wounded men as possible, while he attempted with the remainder of the force to reach Frere station. The engine reached Estcourt, but Captain Haldane was not so fortunate. The men left the trucks and started to run along the line. No sooner did our rifle-fire cease than the Boers galloped down the hill and, before Captain Haldane could realise the danger, they were among the men, and he had no course open but to surrender. The casualties of ‘A’ company were three men killed, four or five wounded, and forty-two prisoners. Private Kavanagh afterwards received the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his gallantry on this occasion. The sound of the Boer guns could be distinctly heard at Estcourt, and great anxiety was felt. A little group of officers assembled in the trenches to the west of the station, and eagerly scanned the country through their glasses. Nothing could be seen, and the firing had ceased. Suddenly through the air rang the shrill whistle of an engine, and at the sound every one gave a sigh of relief. It was the armoured train, and all was well. Another whistle, and round a sharp curve steamed the engine—but, alas! without the trucks. It was evident that a disaster had occurred, although particulars were not received until late in the afternoon; while it was weeks later before the list of casualties could be ascertained. Luckily this mishap occurred when the situation had in other respects improved. The Army Corps was landing, and troops were being pushed forward as quickly as possible. On the 16th, Estcourt was reinforced by the 2nd Queen’s and 2nd East Surreys of General Hildyard’s brigade, and General Barton’s Fusilier brigade was assembling at Mooi River.

The Boers were thus too late, and so lost the opportunity of capturing Maritzburg. Although they doubtless knew of the arrival of fresh troops, they still advanced, and, moving round Estcourt, appeared on the hills to the north-west of Mooi River station. A detachment reconnoitred Estcourt on the 18th, but a couple of shells from Lieutenant James’s naval guns induced them to stay at a distance.

The telegraph line south of the town was interrupted on the 22nd, and for a brief period the garrison was cut off from the rest of the world. But the action of Willow Grange, in which the battalion took no part, caused a retirement of the enemy, who retreated through Weenen on the 24th.

Their retreat was in no degree molested by our troops; but on November 26th the long-desired advance took place. It was an exhilarating feeling to leave Estcourt, and lose sight of those hills and trenches, the scene of so many weary vigils. The army did not, however, make a big stride forward. The advance was only to Frere, some ten miles nearer the Tugela.

As the column started at 8 a.m. there seemed every prospect of an easy day. But on active service it is never safe to assume anything. Although no opposition was met with, and the mounted troops hardly saw a Boer, the progress was very slow, and sunset found the rear of the column still three miles distant from Frere. The battalion had the ill-luck to be in the rearguard, behind a seemingly interminable line of transport. Then the inevitable drift intervened, and waggon after waggon broke down. Finally, part of the transport decided to halt till the morning, and the unfortunate rearguard was obliged to form a line of outposts. As the battalion transport was some distance in front, this meant no blankets, no food, nothing save a limited amount of Natal water. The men were not allowed to consume the emergency rations, and therefore had to suffer from cold and hunger. The night passed somehow, however, and with the break of day we marched into Frere, to find our waggons and obtain food.

Another monotonous fortnight was spent at Frere, the only excitement being the arrival of fresh troops and the building of a temporary railway bridge over the Blaukranz. The arrival of Sir Redvers Buller and his staff gave hopes of an early advance, and everybody discussed what our General ought to do, strategical plans becoming as numerous as sandstorms.

Since leaving Ladysmith, the 2nd Dublin Fusiliers had not been attached to a brigade, and now that the Army Corps had come there were not wanting pessimists who foretold that as the battalion was nobody’s child it would be sent to guard the lines of communication. Early in December, however, it was assigned to General Hart’s 5th, or Irish, Brigade, in place of the 1st Battalion. The latter was ordered to send three companies, with a total strength of 287 men, to make up for the wastage of six weeks’ operations. These companies, which were commanded by Major Tempest Hicks, arrived on December 7th, and were allowed at first to maintain a separate organization, so that the 2nd Battalion had eleven companies.

(standing) and

Capt. E. FETHERSTONHAUGH.

The 5th Brigade was encamped close behind the ridge which lies to the north-west of the railway station. General Hart utilised the fortnight at Frere in making his battalions accustomed to his methods. Every day the whole brigade stood to arms an hour before dawn, and advanced up the slope of the ridge, where it stayed until scouts had reported the front all clear. The General was also very particular about the cleanliness of the camp, and made it a rule to go through the lines every morning.

CHAPTER V

THE BATTLE OF COLENSO.

‘Never shame to hear what you have nobly done.’—Coriolanus.

On December 12th, the 6th and Naval Brigades marched from Frere to Chieveley, and the rest of the army followed the next day. The battalion happened to be finding the outposts, and could not march with the 5th Brigade. Some delay in collecting the companies was experienced, so it was not until 1 p.m. that a start was made, and darkness came on before Chieveley was reached. It was, however, a glorious moonlight night, and marching across the veld had a charm which even the dust could not quite destroy. But romance soon gave way to more worldly feelings when, on arriving at Chieveley about 8 p.m., it became necessary to find the brigade camp among the hundreds of tents already pitched.

On the evening of the 14th, it was known that the army was to advance next day, and attempt the passage of the Tugela. Colonel Cooper assembled his officers in order to explain the Divisional and Brigade orders. He stated that the 5th Brigade would cross the river at a drift two miles west of Colenso, then move down the left bank so as to take in rear the Boers defending Colenso bridge, which would be attacked by the 2nd Brigade. The Brigade orders detailed the Dublin Fusiliers to lead the advance to the river, and afterwards to cover the rear of the brigade when it moved down the left bank. General Hart urged in addition the necessity of keeping the men well in hand. They were to cheer in the event of a charge, but were not to be allowed to make a wild rush.

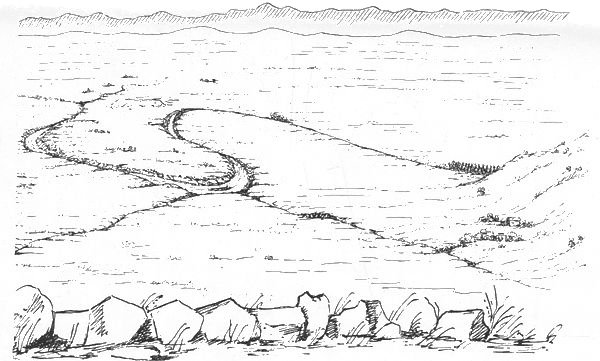

2 miles West of Colenso.

Genl. Hart’s flank attack from the Boer Point of View. 15th Dec/99.

From a sketch by Col. H. Tempest Hicks, C.B.

Every one was early astir on December 15th. Breakfasts were at 3 a.m., but before that hour tents had been struck and packed in the waggons, on which great-coats, blankets, and mess-tins were also placed, so that the men only carried their haversacks, water-bottles, rifles, and 150 rounds. The brigade fell in at 3.30 a.m. It was still quite dark, and the Brigadier spent the ensuing half-hour in drilling his command. The advance was commenced just as the eastern horizon grew grey with the dawn.

The battalion, which led the brigade, deployed into line to the right, and then advanced by fours from the right of companies. In front rode the General with his staff and a Kaffir guide; behind came the other three battalions of the brigade in mass. The deployment of the battalion had brought ‘A’ on the left, and ‘H’ and the three companies of the 1st Battalion on the right.

In this order the brigade moved across the broad expanse of veld, leading to the banks of the Tugela. In front, beyond the river, rose tier on tier of ridges and kopjes, backed by the towering mass of Grobelaar’s Kloof. In the morning light they looked strangely quiet and deserted. Only on a spur to the left front could be seen a few black specks, the figures of watching Boers.

Soon the naval guns in front of Chieveley opened fire, dropping their shells on the horseshoe ridge to the north of Colenso, and into a kraal further to the west. But no answer came. The brigade moved on, tramping through the long grass, wet with the dew. There was a momentary halt in order to cross a spruit running diagonally across the line of march. The ridges in front grew nearer and plainer. They still seemed deserted, although the eyes of many foes might be watching the advancing khaki-clad troops. Behind came the thunder of the big guns, and the shells screamed in the air overhead. It was past 6 a.m. Suddenly the hiss of a shell sounded marvellously close, there was a metallic clang, and a cloud of dust arose some hundred yards in front. It was a Boer shrapnel, and the battle had begun.

Each company of the battalion, without waiting for orders, ‘front-formed,’ and doubled forward. The mounted officers at once dismounted, Major Hicks’ horse being shot under him as he was in the very act of getting off its back. Somehow it did not seem a bit strange to him at the time that his horse should be down, and it never occurred to him then that it had been shot. Another shrapnel burst over the line and then the enemy’s musketry blazed forth, finding an excellent target in the massed brigade, which was deploying as best it could.

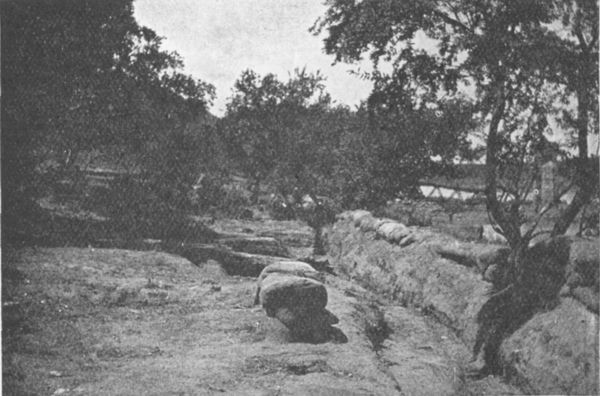

Boer Trenches, Colenso.

The battalion was dangerously crowded together, for it had been advancing as if drilling on the barrack square, although Colonel Cooper had tried to open out to double company interval, a proceeding which the General had promptly counter-ordered. But all did their best. The men rushed forward after their officers, and at their signal lay down in the long grass, whence fire was opened at the invisible foe.

It was very difficult to discover the Boer positions. There was one long trench near the kraal which the naval guns had been shelling, and further to the west could be seen another parapet from which came an occasional puff of smoke betraying a Martini rifle and black powder. But if the Boers could not be seen, they could be both heard and felt. There was one ceaseless rattle of mausers, and a constant hum of bullets only drowned by the scream of the shells.

Capt. Bacon.

Killed.

Lieut. Henry.

Killed.

Capt. H. M. Shewan.

Wounded.

Major Gordon

(1st Battalion, attached).

Wounded.

Second Lieut. Macleod

(1st Battalion, attached).

Wounded.

Casualties at Colenso.

Short rushes were made as a rule, and the flank companies edged away in order to give room for a more reasonable extension. But no sooner had the battalion opened out than it was reinforced by companies of the Connaught Rangers, and, later, of the Inniskilling Fusiliers and the Border Regiment. In a comparatively short time, after the first Boer shell, the 5th Brigade had been practically crowded into one line. Officers led men of all the four regiments, and encouraged them with the cry, ‘Come on, the Irish Brigade!’

There was no control, no cohesion, no arrangement in the attack. No attempt was made to support, by the careful fire of one part of the line, the advance of the remainder; nor did any order from the higher ranks reach the firing line. Small groups of men, led by an officer, jumped up, dashed forward a few scores of yards, and then lay down. Nobody knew where the drift was, nobody had a clear idea of what was happening. All pushed forward blindly, animated by the sole idea of reaching the river-bank.

On the left, part of the battalion was almost on the river when the Boers first opened fire, and quickly reached the bank. After a short halt they turned to their right and moved in single file along the river, being exposed all the time to a heavy fire. They passed through a kraal, and eventually, not being able to find the drift, assembled in a hollow, where they stayed until orders to retire reached them. The centre and right advanced through low scrub into a loop of the river. Some sections of the 1st Battalion, on the extreme right, came upon a spruit, and, under shelter of its banks, pushed ahead of the line.

Thus, by short and constant rushes, the assailants worked their way forward. A brigade of field artillery was supporting the attack from behind, but they found it as difficult as the infantry did to locate the Boers, and most of their shells were quite harmless to the enemy, while a few dropped close to the attacking infantry. They aided the latter indirectly, however, since the Boer guns turned their attention to them.

General Sir Redvers Buller had early recognised the difficulties of the 5th Brigade, and sent orders for it to retire. But it is easier to send a force into a battle than to draw it back. The great difficulty at Colenso was to communicate with the company officers, who had to be left entirely to their own ‘initiative.’ Finally an officer of the Connaught Rangers volunteered to take to the firing line General Hart’s written order to retire. He succeeded in reaching the front, but then, thinking he had struck the right of the line, turned to his left. In reality he had gone to the centre of the attack, and, consequently, the retirement was carried out partially and by fractions. The left fell back about 10 a.m. in good order, though the Boers, as usual, redoubled their fire when they saw their foes begin to retreat. The centre and right, having received no order nor warning, clung to their ground, and in some cases even made a further advance. Section after section, however, gradually realised that their left flank was uncovered and a general retreat of the brigade in progress. A score of men, under the command of an officer, would rise up and double back, causing, as they did so, an instant quickening of the enemy’s fire. All around the running figures the bullets splashed, raising little jets of dust. Occasionally a man would stumble forward, or sink down as if tired, but it seemed wonderful that the rain of bullets did not claim more victims. They claimed enough, however, of the unfortunate three companies of the 1st Battalion, whom the order to retire never reached. Till 1 p.m., and the arrival of the Boers, they lay where they were, suffering a loss of some 60 per cent. When at last Major Hicks realised the situation, he touched with his stick the man on his right, to tell him to pass the word to retire, but he touched a dead man; he turned to the left, only to touch another corpse. One company was brought out of action by a lance-corporal. Then the Boers arrived, and began making prisoners. One shouted to Major Hicks for his revolver; he replied that he had not got one—it was in his holsters on his dead horse—and stalked indignantly off the battlefield, without another question being put to him.

Major Gordon, who was commanding one of the three companies of the 1st Battalion, had been shot through the knee early in the day by a rifle bullet. He lay for two hours or so momentarily expecting to be hit again. After a time he noticed that as long as he lay still no bullets came in his direction, but that the moment he attempted to move there would be a vicious hiss and spurt of sand and dust close beside him. In spite of this he managed to crawl through a pool of blood to a neighbouring ant-heap, which offered some sort of protection, and into which a bullet plunged just as he reached it. Here he remained till the retirement, when, assisted by two sergeants of the regiment, Keenan and Dillon, he managed to hobble away. Even then he noticed that as long as they kept away from the troops who were still actively engaged few bullets came their way, as though the Boers were purposely not firing at the wounded.

The Boer heavy artillery pursued the retiring troops with shells, which made a prodigious noise, and raised clouds of dust, but seldom did any damage. Gradually a region of comparative peace was reached, where the ground was not being continually struck by bullets, and only an occasional shell fell. The extended lines of the 4th Brigade, ordered to cover the retirement, came into view, and behind them the men of the Irish Brigade collected again in companies and battalions. Then, although the artillery was still roaring fiercely, and the mausers rattled with tireless persistence, the brigade trudged back to its former camping-ground, pitched tents, and began to cook dinners. A prosaic but practical ending to an impossible attack.

But there was still one task to accomplish—the preparation of the casualty list: The regiment had suffered heavily. Two officers, Captain Bacon (1st Battalion) and Lieutenant Henry, had been killed, and three, Major Gordon (1st Battalion), Captain Shewan, and Lieutenant Macleod (1st Battalion), wounded. The total casualties were 219, of whom 52 were killed. Among the latter were Colour-Sergeant Gage (mortally wounded) and Sergeant Hayes.

Captain Bacon (1st Battalion) was killed by a bullet, and must have died immediately. He had previously served for a short time with the 2nd Battalion, in which he had many friends, and his loss was bitterly deplored by Officers, N.C.O.’s, and Privates alike.

Lieutenant Henry had scarcely two years’ service, but had in that short space of time endeared himself to every one in the regiment, and was as smart and efficient a young officer as ever joined it. His death must also have been mercifully instantaneous, as he was hit by a shell.

Second Lieutenant Macleod had only joined the 1st Battalion a few days before it left the Curragh on November 10th. He was very severely wounded, his thigh being broken, and although his leg was saved, it was left two inches shorter than it had been, and in the end he had to leave the service on this account.

Major Gordon (1st Battalion), who received a Brevet Lieutenant-Colonelcy for his services, was invalided home, but came out again later on; while Captain Shewan, who had been shot through the leg by a bullet, was back at work again in twelve days, a sterling proof of that devotion to duty which was later on rewarded by the well-merited distinction of the D.S.O.

Group of Twenty Sergeants taken after the Battle of Colenso.

All that remained of forty-eight who left Maritzburg.