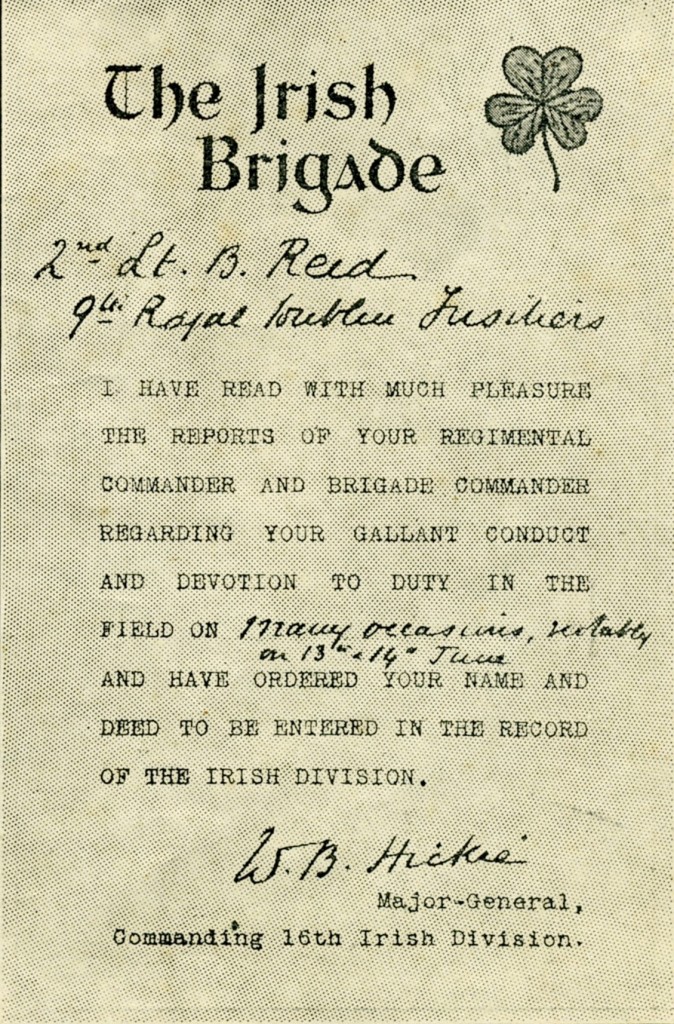

The following letter was written by Second Lieutenant Bernard Reid of the 9th Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers to his parents Michael and Sarah Corrigan Reid, of Tower Hill, Dalkey, County Dublin. It was written on 20 January 1916, a few weeks after both he and the 16th (Irish) Division had arrived on the Western Front. Bernard Reid was killed in action five months later in June 1916 aged 28 and is buried in Vermelles British Cemetery.

We are away from the firing line in back billets and it is just as if we were in training; the memory of trenches is dulled. By a stretch of courtesy we could call it a rest between our spells at the trenches and our next turn in them. I like this place, even if I gave you the name, which the censor forbids, you wouldn’t find it on a map. It is like that everywhere we go. The small, unknown little villages full of the small completeness of French peasant life that are the stability of France, will be well known to us soon, as we pass from one to another.

It was on the night breaking into the New Year that we had (my platoon and another which for the moment was under me) our baptism of fire really and truly. We were moving from the rear trench, from which I wrote that morning to you, to one closer behind the first line. Our road lay through that very famous village which was the scene of a victory some three months ago. As we passed the crucifix, one of those great calvaries the crossroads in France possess, the men, resting their eyes on the black desolated silhouettes of broken houses, and watching their steps now and again to keep from falling into the shell-holes in the middy road, were commenting on the wonderful way this had escaped all injury while the trees and houses near by had all suffered the havoc of artillery. In the road, not more than eighty paces from it we had our experience of what a bombardment is, that seeks one out, meaning to catch one within its malice and crushing cruelty.

We went along in single file on the heels of a guide and had to halt before proceeding from that unsheltered place to some protected place. The guide was unquiet. Our artillery had just broken its hell upon the night. Presently we shall pay for this, we were all thinking, they’ll surely answer in a few moments and they did. The first crashes came as we waited huddled against a wall. The bursting shells threw up earth that descended in showers, shrapnel and other shells came roaring along, you hear them, you can judge the direction by the sound. I was looking out over the open space for them. We dare not move. The men were quiet, not a move out of them, except for the whispering of one to the other. One chap I heard saying “It is awful being here and maybe killed without being able to strike a blow for yourself.” This one is going to the right, that one to the left, this seems right for us, but it stops short and it is a dead shell, it does not explode. I kept telling the men these things and then you hold your breath as one rushes over you and drops just behind crashing through the broken roof and knocking some brick-dust around you. There is nothing for you to do, except to keep a firm grip over everything and wait till the bombardment stops. Forty-five minutes of this seems a long time. It stopped and we came out again on the road. I felt proud of myself and proud of the men, it had been a very trying baptism and those fresh troops had borne it with unimaginable calmness.

As we waited for the Captain to return I learned that during it one man had passed the gate of silence(1). It was a very lucky chance. Soon we are glad to move off again. As we do we pass busy figures showing darkly in the night carrying out the war’s stealthy business and an occasional cry from a sentinel meets us as we pass on. Along a trench, in which you feel safe after the experience of a bombardment, we stumbled rather than walked along for an interminable distance, till with some consciousness of a new starting of things and some strange curiosity, partly devoted to the weary figures passing out, we arrived at our trench proper. In spite of our fatigue, we move with our eyes and senses all curious for what life here is like, what way we are to spend the two days there. The sleeping figures of the men we pass, huddled on fire-steps or under improvised shelters, a waterproof sheet covering them from cold and rain, provokes ones mind, their weariness and their powers of contentment.

I went along after an officer, taking me to where I was to put up, it was a deep dug-out with a fire at the bottom of the steep steps. My load was heavy and it was a blessed relief to throw it off and sit down and take some tea. The couple of officers there were saying it was New Year’s Eve and wouldn’t the German’s usher it in with a great clash of artillery. It is after twelve and nothing has happened. Over a telephone one of them hears a gramophone playing. We all listen. The man at the other end, when he heard there was an Irishman there, asked for him to speak. I did and he then turned on some Irish tunes. I don’t know who he was or how far away. It seemed to me the comradeship of war. I was falling asleep as I was, but we didn’t lie down, the five of us, till 2am.

By the time our two days had passed I had learned to regard the daily routine with curiosity. On the Sunday we were to leave for the first line. I went up to it in the morning. As I and the other officer of the battalion to which we were attached for instruction during those days, arrived there, the Germans started their Sunday severe bombardment. Just as I was at a certain corner a shell (shrapnel) caused a downpour of some earth on top of me. I went round, shells never fall twice in the same place, and I saw one of our own sentries lying a huddled heap of a man, blood pouring from his temple, and a man beside him keeping him up, he died then, he had been hit by shrapnel.(2) We had to go back to our own line quickly, along the communication trench which was being shelled. For two hours our trench was getting the bombardment heavily. The whole time it was going on you occupied yourself, close to the protection of the traverse, judging the direction of the gun on that part, waiting for an indication of a change of direction to change your place. The yell of the heavy shells and the quick unannounced little ‘pip-squeaks’, as the jargon of the trenches calls them, persecute the ears and nerves. The lull brings out again the strange and wonderful silence of the lines of trenches.

You never see a German, you never hear them. There are only a series of scored lines in the ground to tell you that there lie the Germans watching, and here lie you, watching too. In the afternoon, they had their artillery vespers, another couple of hours of ‘strafe’. Here was a little chap only fifteen years old, buried up to the waist by a broken shelter. “I’m in a devil of a fix, sir, and there’s no one to get me out”, shovel and pick were soon in use and there was a pure Dublin accent cheering him up while the possessor worked like a demon digging the lad out. He was clear quickly and was unhurt. One of our men got out from his temporary burial without help or a word. That night we moved up with a certain anxiety to the firing line. We arrived without mishap. There was a sense of shelter in being there. The well built and clear trench, with the great underground life of the place, was a much better place to be in than the line we had left. I had lost my goatskin in the other trench, I had no coat at all, yet I wasn’t cold and although I slept without covering of clothes over me I never felt any inconvenience. The officers we were with were splendid fellows and one felt a regret when they passed out with us, that it should be unlikely for us ever to meet again. We had come to the end of our six days and unwashed, unshaven, unkempt and muddy and tired, we felt ourselves old soldiers and genuine as we struggled back to billets. Anxiety remained till we got clear of the trenches and the approaches, which are shell-swept. As we wandered off past the scene of our baptism, we must all have felt the change in ourselves the great test had wrought, to live the life of the trench, to experience its searchings, to have undergone all it asks of us in adaptation to circumstances, in living so tightly with men of various character, it is a great test of a man. Selfishness is at once found out. The bigness of a man is at once manifest. It adds to one’s self-respect to have lived through it. Passing the village we had gone some distance when, looking back on the signal of the howl of the guns, we could witness the terrible splendour of the shells descending upon the village. It seemed like a grand rain of fireworks, the flash of guns in the night and their red rains. In a while the journey was merely wearisome, end of our night’s journey was all we thought about. It was most welcome when we arrived, some tea, a wash and a sleep.

I lay on a floor of tiles under a roof again and slept as I can always do in trenches or elsewhere, very well. We were in a town for the night’s rest, my billet was a little house. It was my first experience of billets, it was my first contact with the French people in their home life. Since, I have had other experience of it in back billets, as now where I write.

The original marker placed on the grave of Bernard Reid

When on the march the following morning (Thursday January 6th) to our back billets some eighteen miles away, we passed waggons and waggons of French troops on the move also. Sitting beside the chauffeur you would see one chap in his fur coat sleeping, in another waggon the man would be balancing his bottle of wine and cutting chunks of bread and cheese for himself. Inside the waggon Frenchmen were crammed, looking clean and fresh and very gay. Our march seemed to take us through villages like beads on a chain, little places just lying beyond one another at close distances. We halted for lunch just outside one. We were carrying our food. I, having the proper instinct, wandered off a little into the village and found a place where I asked for coffee. I was stopping in the shop getting ready my food and mug for the coffee, but I was invited inside, it was a little parlour, a stove, a couple of chairs and a table. The coffee was ground and made ready while I rested and chatted with the people of the house. We arrived as it got dark at our destination, a poor little, obscure village, where the two half companies joined each other again for the first time since setting out for the trenches. That night we slept in beds, old fashioned lofty things with a forest of wood about them and so short hat we had to imitate a whiting to lie in them. The place was like all the places here, very Catholic and strewn with religious pictures. They are simple folk. The men are away at the war and the women carrying on the business of the farm, the kids are taught their catechism (it seemed to me they never had anything else to learn) in the evening, while the womenfolk knitted. The Irish being so Catholic, as they were surprised to see from the muster at Mass on the Sunday, are well treated but the Scotch, with their petticoats, for which they will never be forgiven, it would seem, they didn’t like. The cure at Mass on the Sunday, at which the soldiers, with all their war accoutrements crowded out the population, started his discourse by saying “I’m sorry the soldiers don’t understand French or that I cannot speak English. We have all heard the Irish Catholics, but now we see what an example they are.”

There wasn’t enough room in that billet, so my friend and myself went away to another little cottage kept by a lone widow about 100 years of age, boasting the name of Roche and eternally babbling dotings about pere Roche, what he used to do, her son, her nephews, relatives, and the furniture, which all dates some fifty years back; the shawl on the bed (it was a wedding shawl) and all sorts of babblement in a difficult high-speed patois which our fatigued courtesy pretended to keep up with by an occasional grunt of pretended understanding. As we’d go in, the doubled-up, fussy creature would pounce upon us, giving us a slap on the shoulder, and away with her and her mad prattling. In the morning she’d give us coffee and at night we’d sit about her stove and hear again the tale of how her husband died, how long she was living by herself and all the recital of the small circle of her life.

It was a ghostly clammy room we slept in, neither of us would sleep there alone, it was much too ghostly a place. There was a shiny spade in the cornder which no doubt had murdered someone and have been polished up as a reminder to others to know better. We never had the courage to ask about it. As we’d go into bed she’d catch us and drag us back, we had passed the holy water font outside the door so we’d have to dip our fingers. As I left the place my friend hesitating between the terror of staying by himself with the ghosts and the rats and hurting the old lady’s feelings by going to a more comfortable place. She washed our things for us and wouldn’t let anyone near them not even our servants. Going away on my journey to this place I have to embrace the old creature.

I left this place on the Sunday (16th). It is a bright little place on the highest point of the province some thirty miles from the line of fire. I found myself a nice billet near our stores as my campaign instinct promted, in a perfect little family. I have a room to myself and a table. At night I can read and feel myself away from all the thoughts of being at war. ‘I hear there’s a war on somewhere’ I heard one of the men saying and it summed up the peace of the place.

(1) The soldier killed in the bombardment was Private Henry Mason, aged 29, from Bray Co. Wicklow. His comrades buried his remains the following night but they were never found following the war and his name is commemorated on the Ploegsteert Memorial.

(2) The sentry killed that day who Reid describes as “a huddled heap of a man, blood pouring from his temple” was Private James Gallagher, a member of A Company from Kingstown (Dun Laoghaire) County Dublin. His name is commemorated on the Loos Memorial.

The 16th (Irish) Division parchment awarded to Bernard Reid