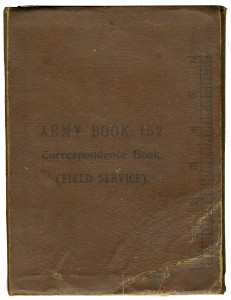

Lance Corporal William McDowell of Cabra, Dublin enlisted in the 8th Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers in March 1915. He served with ‘C’ Company of the battalion on the Western Front from December 1915 taking part at the battles of Guillemont and Ginchy amongst others. In his official Army Correspondence Book he made notes of his service including details of his comrades and his own particulars of service. In the following account he describes an interesting aspect of work carried out my members of the Dublin Fusiliers outside of the trenches and which is less well known and recorded. Fatigue duty was a common part of the life of a First World War soldier and this account comes from McDowell’s last month of service at the front, as he was sent home in March 1917 and later discharged described as being “no longer psychically fit for war service”.

Plateau siding, near RIver Somme Feb: 1917

I carried this book in my haversack in Feb. 1917 in France. I was sent down from the Somme trenches (at Guillemont) with a party of ten men of the R. Dublin Fus. on a fatique – viz. Loading shells on ammunition carts from the trucks which came up on a specially constructed ‘siding’. The shells, bombs, grenades etc. were of all kinds and sizes and were temporarily stored in four wooden magazines along the track. There were bomb proof shelters also for the workers (which I never saw) The work was very hard and the weights to be carried very heavy, 15 in. shells, No. 5 Mills Bombs etc. but the food was good (compared with the trench diet) and rum and cigarettes were fairly plentiful, too good to last. After about 9 or 10 days (we worked from our hut, a large shelter with a door at each gable end and no windows covered with a corrugated iron roof) we got the order one evening to stand by and go to our hut, a ration of rum thrown in, and we stood by all night. ‘Monsieur Boche’ be thanked for the rest. We commenced work by flares at night and got a lot done, knocked off, and then at about 2 or 3 a.m. it happened ! Four or five of the trucks were loaded with high explosive shells and then the first bomb came from overhead. I heard the plump and the 5 inch shells hit the first batch of trucks. I got up and found that I was alone, so I dropped Rabelais (I had been reading with a carriage candle) and ‘got too’. I didn’t wait to dress. As I left the hut the first explosion of a truck of ammunition took place and I was simplt flattened into the mud which was fortunately soft (the first time I appreciated it) and things like truck wheels and axles started to rain down. I managed to get up and got another 200 yards more or less, it felt like 100 miles and got cover under a bank, when one of the magazines went up ! I buried my head in mud and held my ears in anticipation.

After this I got several of the men together and we got a disused shelter from a small company of the Labour Corps. Also some rations, biscuits, bully beef, rum, tea and even smokes. Charcoal for the fire (made of a biscuit tin) and we took up our quarters on the floor around the store, made tea, ate and were comfortable. I discovered that in the corner where I took my place to sleep that there was a dead soldier lying there. Strange how still the dead, you would at once notice notice a sleeping man though the breathing movement be scarcely noticeable. Anyway we were too tired and too used to dead men to care and I slept about 14 hours. We returned next day to the siding and found that it had practically disappeared so they sent us back half naked to camp without boots, rifles or equipment. I got a sick man’s equipment and boots and proceeded once again to the trenches.